Almost a million British soldiers died in the Great War. Some died alone, killed by a chance shell, grenade or bullet; many died together as they attacked or defended against attack. Thousands of men died of wounds they had suffered, at the medical facilities along the casualty evacuation chain. Many died of illnesses or accidents. This is all well-known and well documented: but what actually happened to them after they died?

4945.jpg)

From the photographic archive of the Imperial War Museum, with permission: The bodies of men killed in fighting near Guillemont Farm lie with their grave markers awaiting burial, 3 October 1918. IWM negative E(AUS)4945. Note the stacked stretchers

Men who were killed in the fighting area

The varying nature of men’s deaths in the front line and the specific conditions at the time of their death meant that their ultimate fates differed widely. For example:

– some men would have been identifiable and probably buried close to the front line. This would have included, for example, men killed by a sniper or shell explosion whilst holding a trench or on a road close behind the lines; men dug out of a collapsed mine, trench, sap or dug-out; and men dying of wounds having begun their evacuation, but whilst still in their Battalion or Brigade area. These men would be identified by comrades, NCOs or officers.

– some men would have been less easily identifiable, but probably buried in cemeteries or burial plots still quite close to the firing line. This might typically have included those men who had attacked and been killed or died of their wounds, but whose bodies could not be brought in because the place they were lying was under fire. Eventually when the fighting moved away, their bodies would be buried if possible. In this category too would be men who died in a successful advance, whose bodies would be cleared by units other than their own. Identification would be through pay books, tags, and other physical means by men who did not know the individuals.

– some men would be unidentifiable, if the damage to them was such that they ceased to exist as a body or where any form of identification had been lost. Fragments of men, once found, would be buried if possible.

– many men were simply not found, although post-war battlefield clearance (see below) reduced the total of missing.

Many thousands of small burial plots were created on or very close behind the battlefields. They were often damaged by shellfire, and in 1918 many were over-run first by the advancing enemy and later by the Allies pushing eastwards again. Plots were destroyed as the ground was shelled, and the locations of many graves that had been registered and known about were made uncertain.

See our article on “reading” a cemetery, for the type and layout of the cemetery and the wording on a man’s gravestone reveals much about his death and burial.

Men who died on the casualty evacuation chain

See our article on how casualties were evacuated and treated

Cemeteries were created at most of the places where the Casualty Clearing Stations and the less mobile Base Hospitals were located. These cemeteries were rather more orderly in terms of layout, tended to be rather larger due to the concentration of death, and some had the benefit of attention to the grass and flowers around the graves. In most cases, the man was identified and usually his burial was attended by a Chaplain. Some of the these cemeteries suffered from shellfire or other damage, particularly as those laid out in 1914-1917 were overrun by the enemy and then the counter-attacking Allies in 1918.

How the next of kin were informed

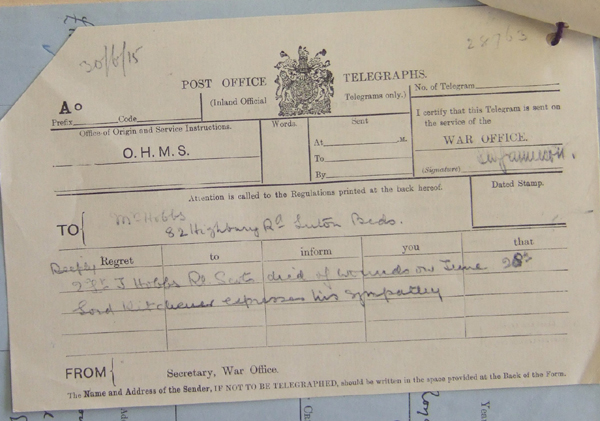

Once the man was confirmed dead, the next of kin were informed of the terrible news. Officers next of kin were informed by telegram:

From the service record of 2/Lt J. Hobbs, held at the National Archives. Crown Copyright.

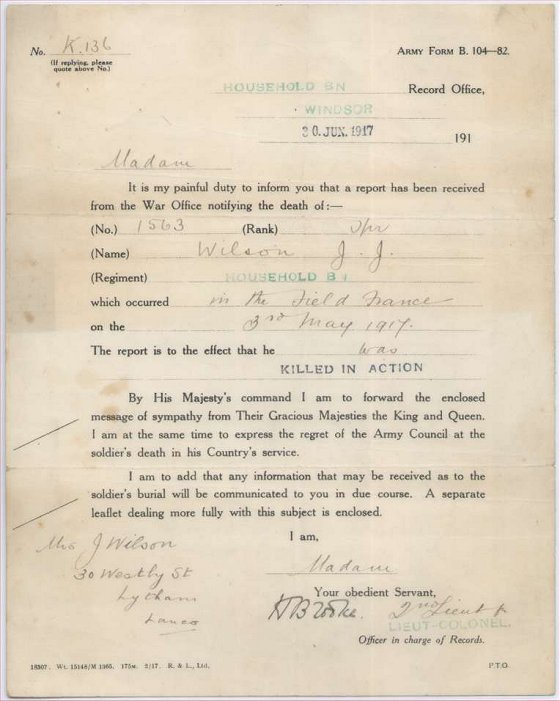

Next of kin of men of the “other ranks” were informed by receipt of this Army Form B104-82:

With thanks to David O’Mara for this image and the one below

In the battlefield conditions of the Great War, it was not always possible to be sure if he was dead. Men were often simply not there are were officuially recorded as “missing”:

Official enquiries would be made via neutral channels to see if the man was in enemy hands as a prisoner of war, or that the enemy had definite knowledge that he was dead. After six months had elapsed with no news from this enquiry, the next of kin would be contacted to see if they had received any further information from friends or comrades. If not, the man’s death would be presumed to have taken place on the last day he was known to be alive.

The Graves Registration Committee

In the earliest days of the war there was no organisation responsible for the marking, recording and registration of soldiers graves other than the man’s own unit. In October 1914, a Mobile Ambulance Unit provided by the British Red Cross and headed by Fabian Ware (it had previously been operating as a medical unit with the French Army) began to undertake these duties on a voluntary basis. Soon enough, the unit found that the need for graves registration so large, and the growth of army medical units so rapid, that is was able to concentrate solely on this task. Prior to 11 November 1918, graves registration was the responsibility of the army in the field. The following information is extracted from the Adjutant Generals Instructions to the BEF:

The establishment of permanent graves was afforded by the French Government by law on 29th December 1915. France provided land that would be maintained in perpetuity for British war dead. The Director of Graves Registration and Enquires (DRG&E), as representative of the Adjutant General, had sole and global responsibility to work with the French Government for the establishment of these cemeteries. The office of the Director of Graves Registration and Enquires was located in Winchester House, St James, London. Below this office each Field Army had a Deputy Assistant DRG&E. Grave registration in the field fell squarely on the shoulders of the unit Chaplains. They were responsible for filling out the proper form (AF W3314) that included the information about the grave, and forwarding to both the DADGR&E and the DAGGHQ 3rd Echelon. Information submitted included map references using the 1/40000 or 1/20000 trench maps, or detail descriptions of localities on the back of the form, in addition to the usually expected basics such as the man’s name, unit etc. He was also responsible for the marking of the graves. However, many dead were interred into already authorised cemeteries. In this case special instructions were issued as each authorized cemetery was usually under the care of a Graves Registration Unit. The actual interment of graves was up to the unit. The term “unit” could mean many things; internment by the unit of the actual casualty, internment by Casualty Clearing Stations, Field Ambulances, General Hospitals, Graves Registration Units etc. Grave registration units were non-permanent units, that is some lucky unit was detailed to perform that task and it could be any one. Basically graves registration was the responsibility of the unit responsible for the casualty or the unit finding the casualty.

From the photographic archive of the Imperial War Museum, with permission: WAACs tending the graves of fallen British soldiers in a cemetery at Abbeville, 9 February 1918. Photograph by Second Lieutenant D McLellan. IWM negative Q8467.

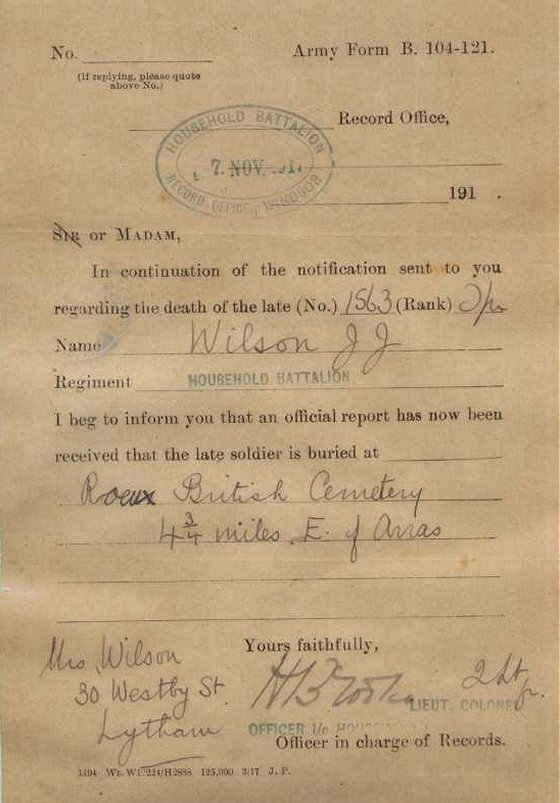

How next of kin were informed of place of burial

The work of the Graves Registration Units allowed a system to be set up whereby the next of kin could be informed of the place of burial of the soldier.

Army Form B104-121, kindly provided by David O’Mara.

Post-war clearance of the battlefields

After the war, certain parts of the battlefields were taped out into grids and searched at least six times. This activity went on well into the 1920’s, on a large scale. The search parties (Exhumation Companies) did not dig over all of the land marked out by the grid. Instead, they looked for clues that indicated that a body or bodies could be buried there. For example: rifles or stakes protruding from the ground bearing helmets or equipment; partial remains and equipment that had come to the surface; small bones and pieces of equipment brought to surface near to rat-holes; discolouration of grass, soil or water. (Grass was a more vivid colour were bodies were buried and water turned a greenish-black). Once a grid had been searched and possible bodies marked then the gruesome task of exhumation began. Remains once discovered were put onto cresol soaked canvas for a careful identification. If any uniform remained, pockets were searched and badges and buttons identified. If a Scottish soldier was found, the tartan was recorded. Next they looked for identification discs and personal effects: watches sometimes had useful had inscriptions, for example. Sometimes knives, forks and spoons that had been placed down the puttees carried the man’s name, initials or number. Webbing was checked because that also often had soldiers names and numbers stencilled on. If the remains were deemed to be an officer (Bedford cord breeches and privately bought army boots being a good indication) and the skull or jawbone was intact then a dental record of the teeth, fillings, false ones etc was also made in an effort to confirm the identification of the man. The remains would then be taken to one of the cemeteries that was open for burial. Thus many of the small wartime burial plots were expanded with the post-war additions; indeed many bodies were exhumed from small cemeteries and concentrated into larger ones. Those remains that could not be identified were buried as an unknown soldier.

With thanks to Terry Carter for the information in this section.

Human remains are still being found on the battlefields to this day.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission

The war time Graves Registration Units eventually developed into the Imperial War Graves Commission and henmce to today’s Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Funded in proportion of their dead by Great Britain, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, India and other states, it carries out the care and maintenance of the cemeteries and memorials of not only WW1 but all subsequent conflicts. Most visitors to the battlefields never cease to be impressed by the standard to which they are kept, and long may it remain this way.

Immaculate, as they always are thanks to CWGC, this is Guillemont Road Cemetery, not far from the village of that name on the Somme battlefield. Author’s collection.

The War Graves Photographic Project is collecting photographs of every headstone.

The missing who have no known grave

Those soldiers who were missing and presumed dead are listed on the major memorials in the theatres of war; in this way every man is commemorated even if no trace was ever found of his physical remains.

But not all men were recorded, for a relatively small proportion were simply missed by the administrative processes of the time. An excellent project is underway to determine who they were and to carry out the necessary processes of proof in order to have their names commemorated at last: the “In From the Cold” Project.

Links

Records of men who lost their lives

How reliable are dates of death? The case of Arbroath man James Milne