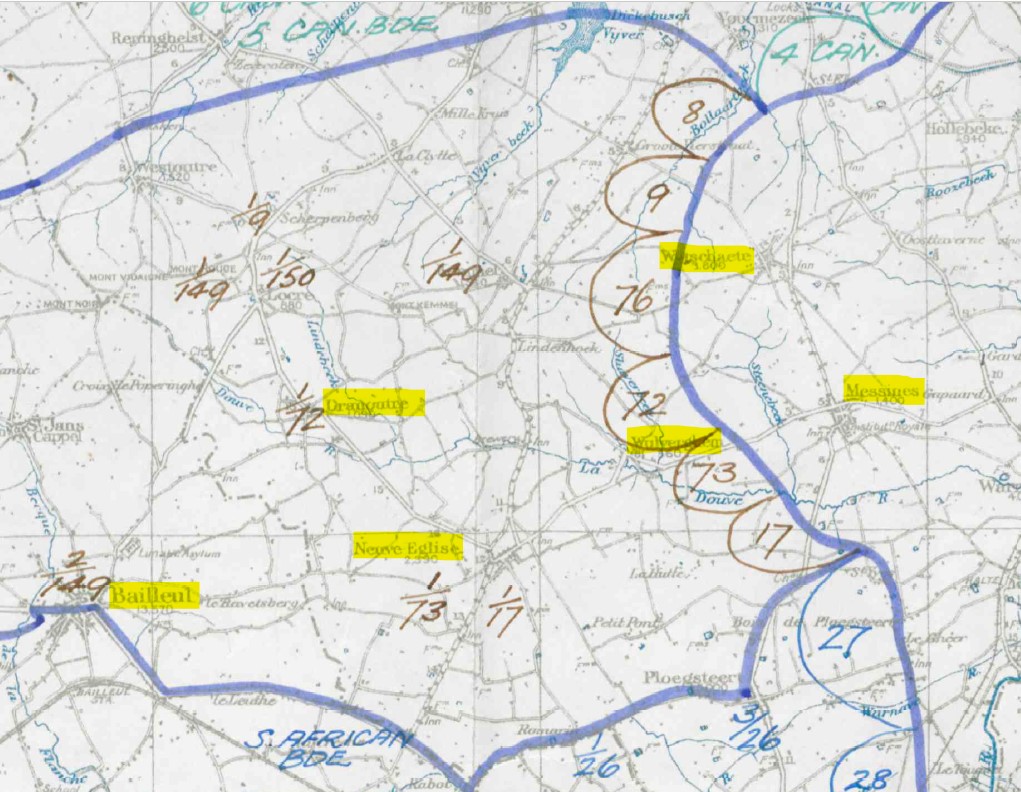

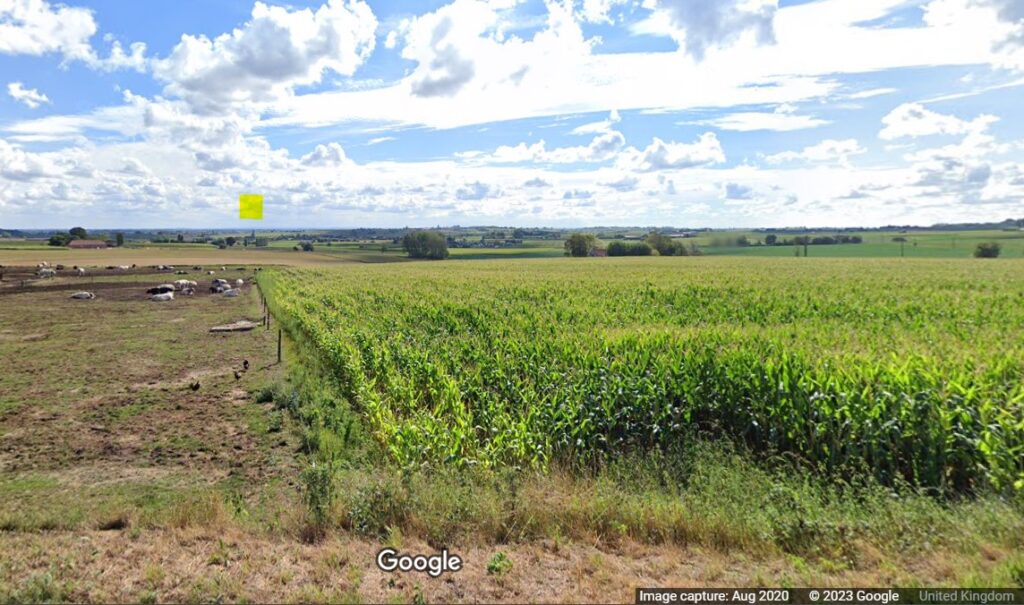

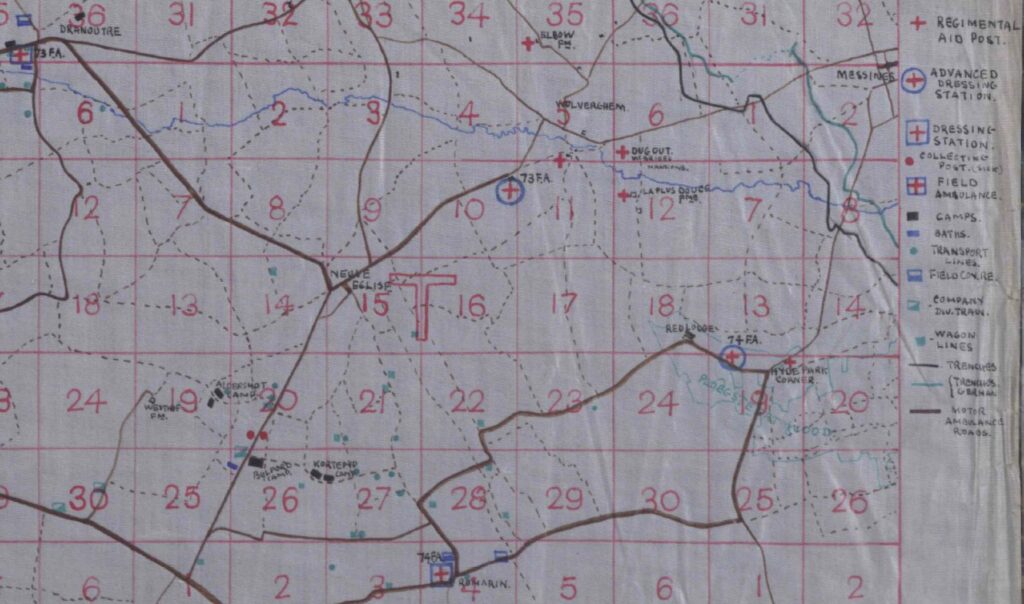

This page decribes an action that took place on the front held by V Corps (under command of Second Army), south of Ypres and on the lower slopes of the Wytschaete-Messines ridge. On this front, the situation on the corps front in the days before the attack was relatively quiet, although there was much artillery fire in both directions, and German aerial bombing of Bailleul.

Intelligence

From the General Staff at 24th Division headquarters, which had moved from St. Jans-Cappel to Bailleul on 18 April.

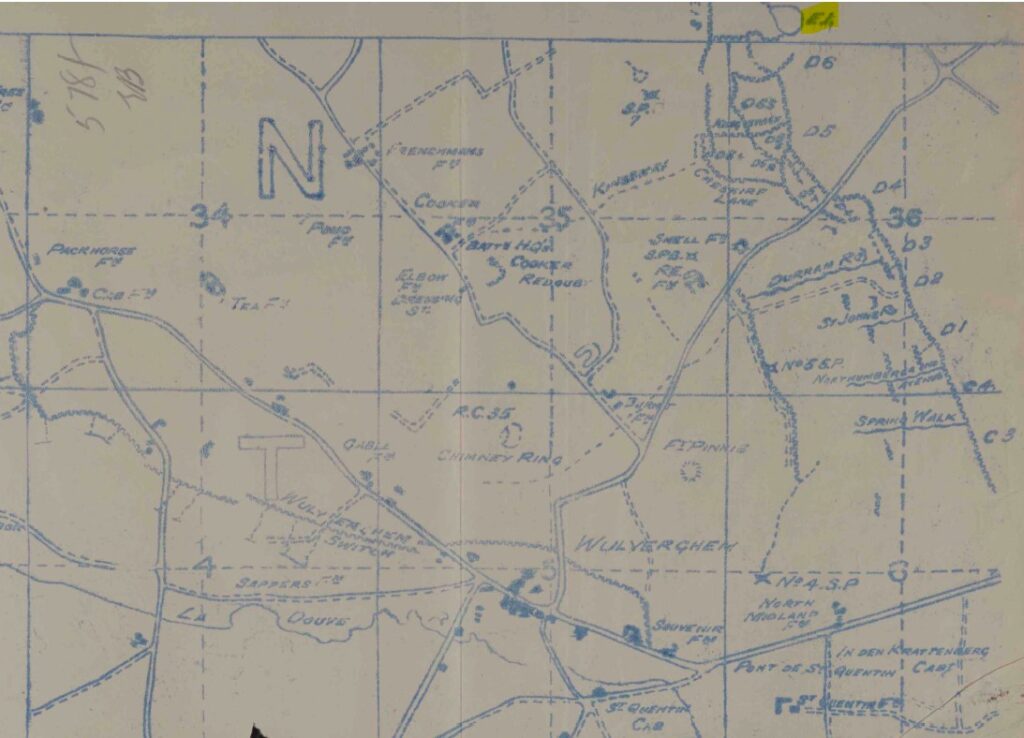

- On 21 April, divisional artillery reported that it had broken two gas cylinders in the German trenches at grid location N.36.a.6.8. The gas floated down into the area then held by 50th (Northumbrian) Division and one man was gassed. [The location is SW of the ‘In der Kruisstraat Cabaret’: see Canadian map, below.]

- Information came from 3rd Division on 26 April that the Germans were waiting for a favourable wind to make a gas attack on V Corps front. All ranks were warned. A false gas alarm came from 9th (Scottish) Division’s area on the night 26-27 April.

- In the evening of 29 April, two German deserters came across to 3rd Division, stating that a gas attack would be made early next day. Again, all ranks were warned.

The attack

From the General Staff at V Corps headquarters (at Bailleul):

- At 12.45am, 9th Infantry Brigade of 3rd Division reported a gas attack.

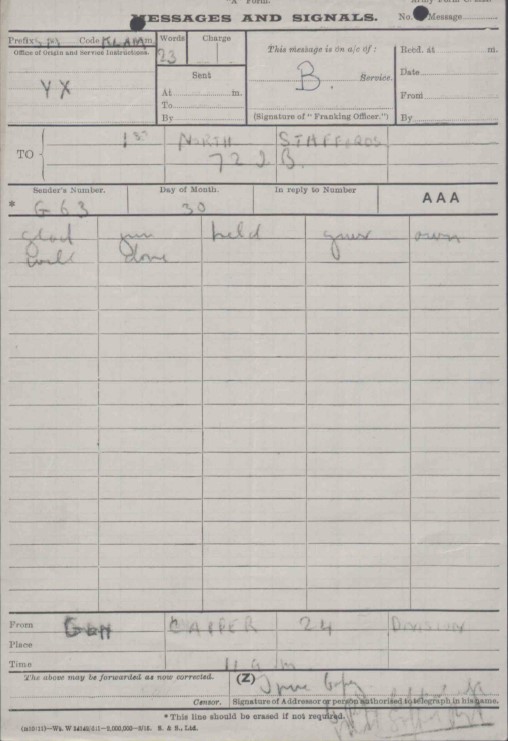

- 24th Division reported that at 1.05am, an SOS signal was sent up by the 2nd Leinster Regiment at U.1.central and North Staffordshire a gas alarm at N.36

- 3rd Division reported at 1.20am that a gas attack had started against its right brigade at 1.50am. No gas was reported against its left brigade. Three minutes later, division reported that a German deserter had said that an attack was to be made in considerable strength, possibly two corps, and if the front line was easily taken then its objective would be Kemmel.

3rd Divison

From the General Staff at 3rd Division headquarters (Westouter):

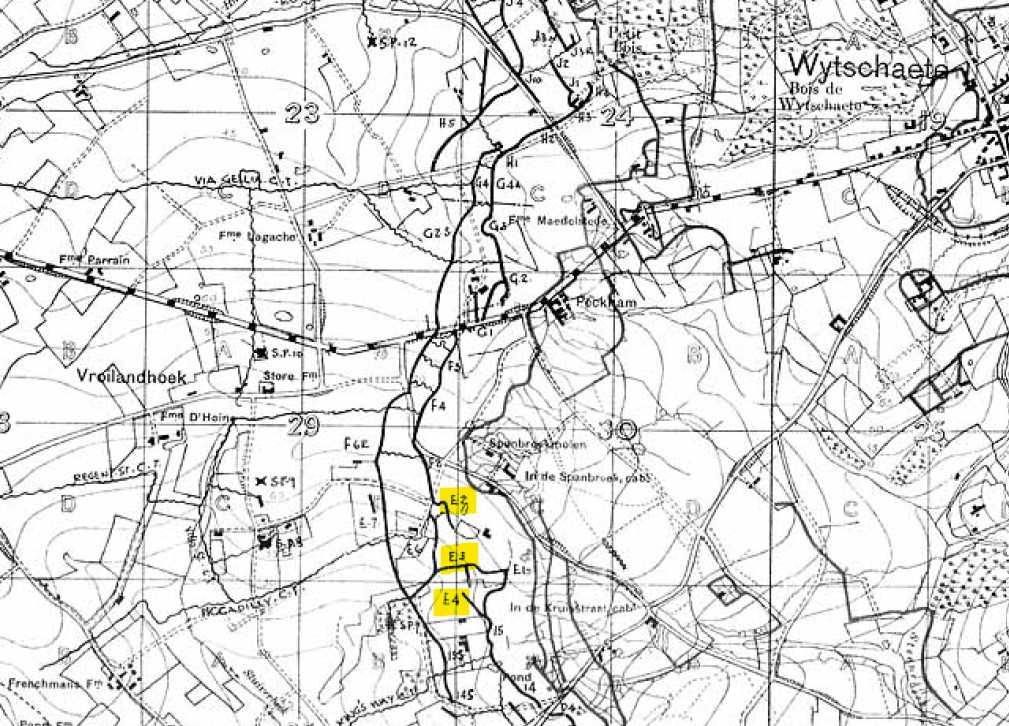

- At 12.56am our centre brigade reported an enemy gas attack, accompanied by artillery fire. Our guns immediately opened fire on the enemy and gas alarms were sounded. So far as our front was concerned, the effects of the gas were confined to the battalion on our extreme right. Here the enemy attacked and succeeded in penetrating the “Bull Ring” [near E1] but the 10th Royal Welsh Fusiliers counter attacked immediataly and drove him out. By 2.45am all was quiet again.

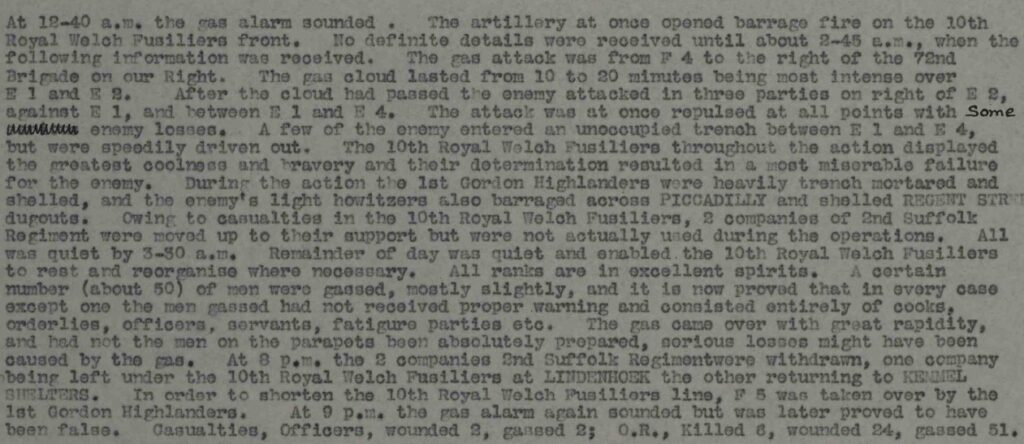

From the war diary of the headquarters of 76th Infantry Brigade (Kemmel):

- At 1.40am the gas alarm sounded. The artillery at once opened barrage fire on the 10th Royal Welsh Fusiliers front. No definite details were received until 2.45am. The gas attack was from [trench name] F.4 to the right of the 72nd Brigade on our right. The gas cloud lasted from 10 to 20 minutes being most intense over E.1 and E.2. After the cloud had passed the enemy attacked in three parties, on right of E.2, against E.1, and between E.1 and E.4.

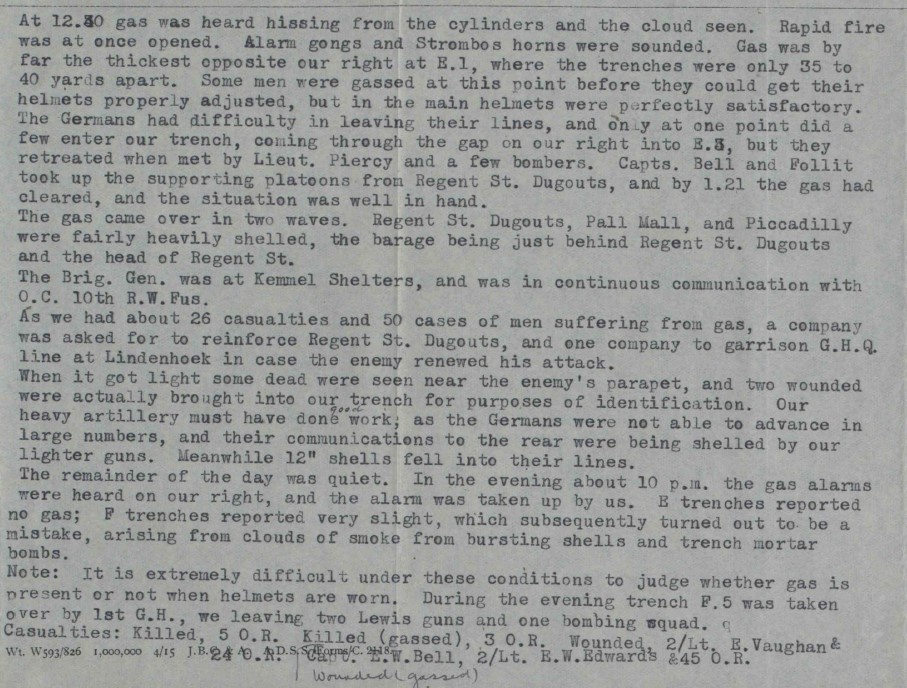

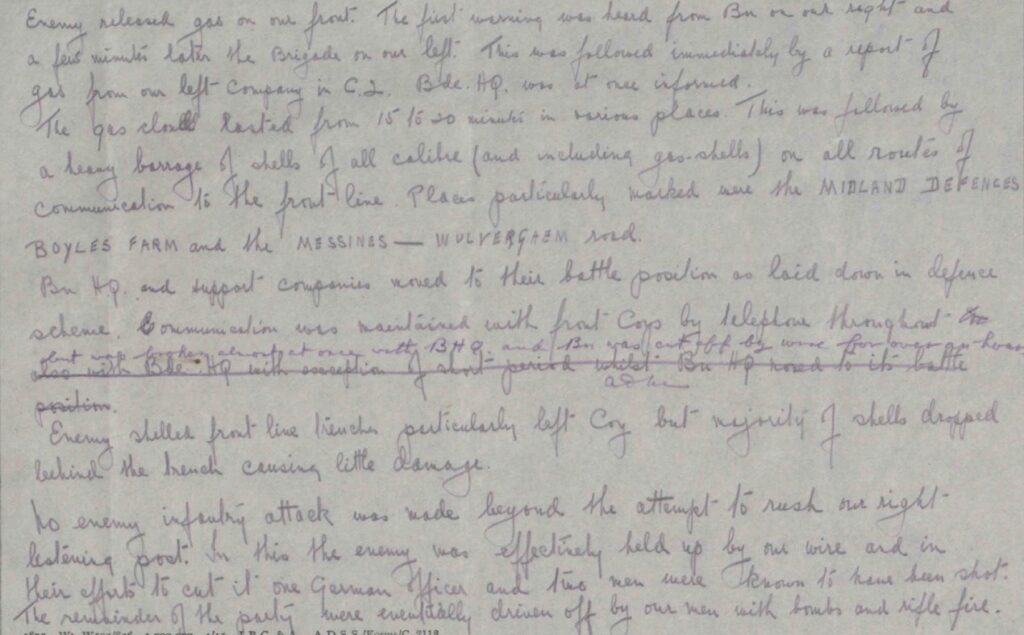

From the war diary of the 10th Royal Welsh Fusiliers:

24th Division

From the General Staff at 24th Division headquarters (Bailleul):

- At about 12.30am [30 April] the enemy started a gas attack on the left and centre brigades, and on the right of 3rd Division. The gas lasted 15 minutes, and was worst opposite our D and C, diagonal, 140, 139 to 135 Trenches. Within 10 minutes of the cessation of the gas, the enemy forced an entry into the D.4 salient with a small party, who were bombed out by the North Staffords. The enemy endeavoured to blow up a disused mine shaft but had not the time to do so: a half-hearted bombing attack was made on C.3 and 4, and also against the Leinsters in the diagonal. The enemy’s artillery shelled some of our supporting points … and a strong barrage from Cookers Farm to RE Farm. The divisional reserve was ordered to assemble in the vicinity of Bus Farm, but by 5am the situation was normal and the units returned.

- At about 10pm there was another false gas alarm coming from 3rd Division (it appears to have stemmed from some heavy artillery fire that included gas shells). 24th Division stood-to until shortly after 11pm.

From the war diary of 72nd Infantry Brigade (which contains an excellent, detailed defence scheme for this area):

- The enemy released gas at 12.35am opposie the whole length of the brigade front except a smal strip opposite D5 and a part of D4 [probably as gas in that area would have to pass over a small height in the German lines known as Muskrat Mound]. At the same time, heavy rifle and machine gun fire was opened against the length of our line, accompanied by shrapnel. The salient D4 was chiefly engaged. A barrage of minenwerfer [German mortars] was put up immediately in rear of D4. Barrages were also set up along the lines St. Quentin Cabaret – Wulverghem – Burnt Farm – Cooker Farm – Battleaxe Farm – RE Farm.

- At 1.20am or later, the enemy attacked our salient D4. At the same time he appeared in front of his trenches opposite D5 and D6. It is not known whether he left his trenches opposite the 8th Queen’s [our right battalion] except opposite the right of D2. At this point a patrol came within bombing [hand grenade] distance of our parapet. The raiding party [at D4] is judged to have consisted of some 80 men, in parties of 5. [Their bombing party, taking advantage of a crater to hide their approach] put out of action, at their first throw, the garrison of the most advanced bay of the salient. More parties came across and bombed outwards. Their further advance towards D% was stopped by one of the Lewis Guns of the 1st North Staffords ,,, and a counterattack cleared the enemy from our trenches.

From the war diary of 73rd Infantry Brigade:

- 12.45am. Message received that the enemy had released gas in front of Trench 142. At 12.40am SOS from Left battalion [2nd Leinster Regiment]. Action taken as per Defence Scheme.

From the war diary of 2nd Leinsters:

Casualties

From the General Staff at 24th Division headquarters:

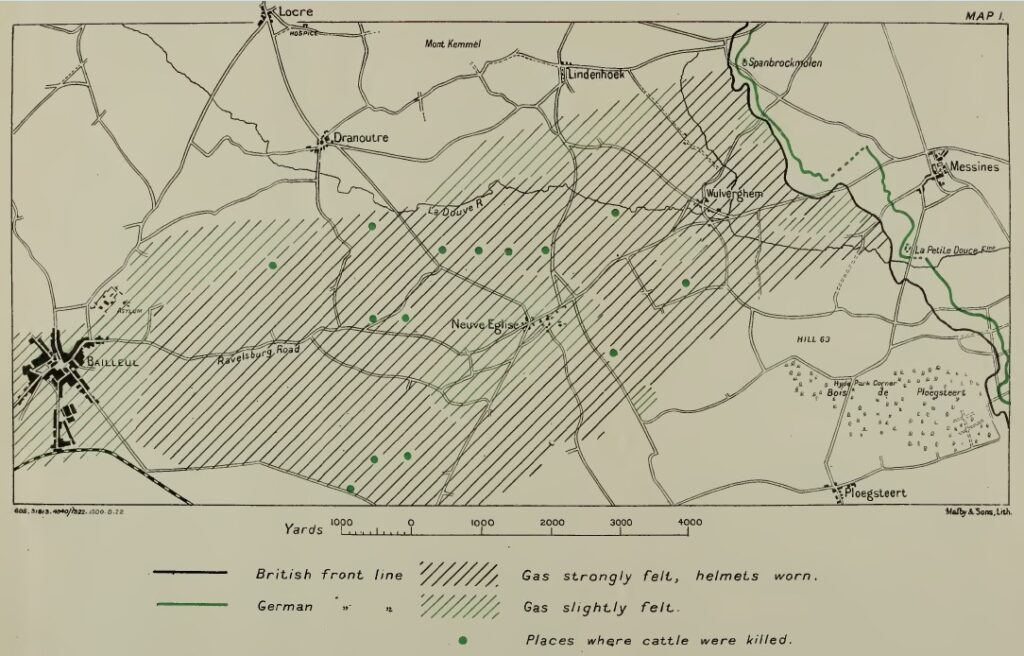

Our casualties were very heavy, nearly 400 killed, gassed or wounded. The enemy’s gas was very effective, the wind bringing it over our liners at a pace about 15mph. The gas extended all over our back area right up to Bailleul.

From 72nd Infantry Brigade:

- Casualties 8th Queen’s 52 gassed, 32 wounded; 1st North Staffords 86 gassed, 32 wounded.

From the Assistant Director of Medical Services, 24th Division

- Altogether 338 cases of gas poisoning received and 190 wounded. Collection ane evacuation caried out by 73rd and 74th Field Ambulances very satisfactory. The gas is considered to be the same as that used in former attacks on this front.

- Up to 9.30am (1 May), 344 officers and men [belonging to this division] had been admitted to 3rd Casualty Clearing Station here [Bailleul] and of these 27 had died and more here [are] dying. At the 73rd Field Ambulance [Dranoutre] 10 had died.

- The new PHG gas helmet is difficult to put on, causing delay, and the eye pieces are much too far apart, rendering vision very difficult.

73rd Field Ambulance recorded receiving 350 patients between 3.30am and noon, of which 226 were suffering from gas poisoning. More continued to come in during that day and the morning of 1 May. By 2pm that day, all had been cleared from the dressing stations.

74th Field Ambulance reported that Chlorine could be smelled in Bailleul at 2am and within a few minutes in became marked. All available ambulance cars were sent to the dressing station at Romarin. 19 gassed (who all came in from the Wulverghem area) and 47 wounded came in. Two Royal Engineers were slightly gassed in Bailleul.

On 1 May 1916, Second Army’s Director of Medical Services stated in the war diary that 24 men had died in Casualty Clearing Stations from the gas, and a further 25 in the field. He also noted that numerous rats had been gassed in the trenches, and three cows in Bailleul.

Why were so many men gassed?

Gas was not a new weapon by April 1916. There had been recent alerts and it was known that there were gas cylinders in the German trenches. The men had been issued with gas helmets. So why did it come as a surprise and affect so many men?

The war diary of the General Staff at 3rd Division headquarters includes a report from Captain E. L. Reid of the Royal Medical Corps, who made a study by asking the casualties how they came to be gassed. He noted cases of men in the front line who received the gas before they heard any alarm; others in dugouts or emplacements who simply did not hear an alarm; men who had helmets on but could not get them tucked in and properly adjusted in time; bombers whose throwing action dislodged the skirt of the helmet; men who could not see through the eyepieces and briefly removed the helmet to do so; that some were affacted after the main gas cloud by sitting in dugouts or other places where the gas hung around.

Reid also noted that many men who passed through the dressing stations were “slight” cases, whose brass buttons did not gain the “light bluish mildew-like deposit on them” that was sympomatic of cloud gas, and who “presented none of the ashen blue complexion, the pained and troubled expression, the laboured respiration with violent spasmodic efforts to rid their lungs of the tenacious yellowish green frothy fluid which was threatening to drown them, or the fixed staring eyeballs with their lids half closed.” They were “well except for red sore eyes and a tight feeling at their throats.”

Sources

War diaries as mentioned in text

Canadian war diary – Library and Archives Canada

London Gazette

Links

Sir Douglas Haig’s first despatch (briefly covers this action)

Tragedy unfolding: the attack on Spanbroekmolen 12 March 1915